The Orchestra Model (OM) guitar is the result of a collaboration between the C.F. Martin Guitar company and a jazz-era banjo player from Atlanta named Perry Bechtel. In the late 1920s, the days of the banjo as a very popular instrument were coming to a close, and banjo players like Bechtel were migrating to guitar. So Bechtel suggested to Martin that a longer, banjo-style neck would really appeal to banjo players. Up to this point all Martin guitars — and since most manufacturers copied Martin’s designs, this meant “most of the guitar-making universe” — had a neck that joined the body at the 12th fret. This limited the player’s access to the upper notes on the fretboard.

Perhaps people had designed guitars with more neck available to the player, but guitar making is about trade-offs, and I suppose the old design that featured more soundbox, rather than more neck, was judged optimum. Guitarmaking is a very traditional craft and I imagine that 100 years ago all the builders thought that the best ideas had already been done. Even today, the would-be innovator is warned away from innovation by the experts. They say, “Well, smart people have been building guitars for a long time now, and all their good ideas have been consolidated into the current state of the art, which does indeed look a lot like a guitar made 80 years ago. That’s the proof of our proposition. Just look at the violin for further testament. No one has improved on Del Gesu and Stradivari. And those guys are long dead. So why try this new thing? Surely it was done by one of the old guys and was a failure. We know it was a failure because it’s not part of the tradition. And like we said, the tradition is the best of everything that works.”

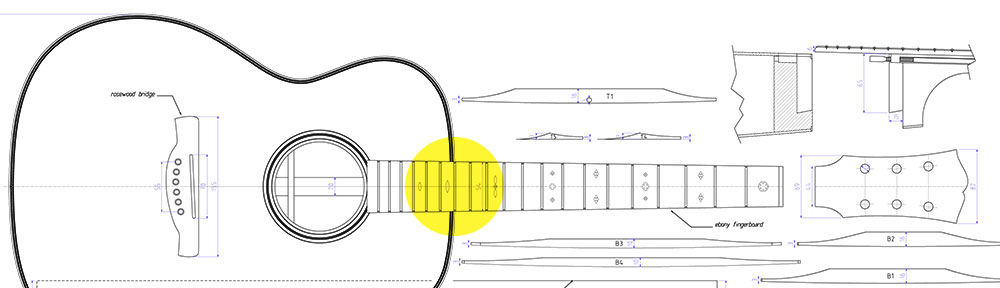

Martin Guitar looks to be both the Guardian of the Sacred Tradition and also the Reckless Innovator in the steel string acoustic guitar world. I guess that’s a good way to keep a respected, vibrant business going for close to 200 years, but it’s a fine line. So Bechtel got someone at Martin interested in his idea. It must have been a slow week at the factory. Martin’s solution was to move the bridge closer to the neck join and shorten the body above the soundhole. So we have a smaller body but we haven’t taken much away from the chief sound-producing area below the soundhole. The banjo players got back some of the neck real estate they were used to playing. Martin also used a 1/2-inch longer scale length on the OM, which was still a bit shorter than the average banjo scale length. Here’s a photo from Robert Corwin’s vintagemartins.com showing the older style 000 12-fret body on the left and the new-at-the-time OM body on the right. Both guitars are the same width across the wide part of the body, the “lower bout.”

The OM design came about as Martin was in a transitional phase. Their older gut-stringed instruments were giving way to demands from players for steel stringed guitars. Steel strings were louder and cut through a mix of other instruments better than gut strings. It’s some kind of irony that the players wanted the extra volume to be heard above the banjo players, just as the banjo players were moving en masse to the guitar. Anyway, it turns out that the smaller body with the bridge moved up and a longer scale length was a design that increased the sharpness of tone and really established its own space in the orchestra mix. The 14-fretters were just brash. And when you’re playing guitar in a loud orchestra, brash is better.

At about the same time as they were developing the OM, Martin was experimenting with a larger guitar. They referred to it as a “bass guitar.” And later named it the “dreadnought.” The dreadnought was 15-1/2 inches or so across the lower bout and had a wider waist than the OM and was longer and deeper, giving it a lot more soundbox volume to produce that big bass. The dreadnought started off as a 12-fretter but soon adapted the 14th fret design of the OM. I suppose the target customer for the bass guitar was the guitar player in the string band — the more rural musician, the cowboy crooner — not the orchestra player. The dreadnaught was so successful that now it is the icon of the steel-string guitar world. Orchestra and jazz players went on to adopt the archtop guitar. Smaller sizes like the OM and 000 fell out of favor and were only manufactured in small quantities as of the late 1960s.

About the name “dreadnought”: yes, it was the name of the biggest, baddest class of battleship at the time and thus Martin could glom onto that attitude for its outsized new guitar (look out banjoists!), but I also think it was a play on words uncharacteristic of the stern German heritage of the Martin company. Everything about the dreadnought was uncharacteristic of the Martin tradition. Since naming their largest new design the “0” size in the mid 1850s, Martin had been averse to increasing the size of the guitar. This large 0 size was only suitable for the concert stage, not the casual strummer in the parlor, or so they said in their sales literature. The size 5, with an 11-1/4-inch lower bout, was their smallest model, and the models got larger from there while the names got consecutively smaller — size 3, 2-1/2, 2 and 1. The model numbers are moving inverse to the actual sizes. So when you get to the 0 size, well that’s just a big as a guitar should ever be.The 0 size is 13.5 inches across the lower bout — a full two inches smaller than the dreadnought.

Over the 70 or so years between the advent of the 0 and the dreadnought, the crazy customers had wanted larger guitars. Martin had made progressively larger models and named them the 00 and the 000. The 000 was 15 inches across the lower bout. I suppose the dreadnought name was intended to get them out of this silly namegame where you add another zero to the new product name every decade or so. Looking down the road you see a 00000000? So the dreadnought was the proper way to blow this inverted nomenclature business out of the water. This is a respected family enterprise, so you don’t go around saying, “Damn, why did granddad put us in this mess of having all these zeros in the model names? Was he nuts?” They couldn’t change the older model names, but they could put a stop to the naming convention. How does it fit in with the many zeros of its siblings? Anyone remember Jethro doing his “ciphering” on episodes of The Beverly Hillbillies? He didn’t say “zero,” he said “ought.” 1904 was “nineteen-ought-four.” This was common parlance in 1930. Sizes 0, 00 and 000. Okay, say it with me, “single ought, double ought, triple ought, dreadnought…” Pretty much the end of the “ought” line.

After a few years on the market, the OM was changed to a shorter scale length. The assumption is that the replacement steel strings that people were using were really heavy compared to today’s strings. The damage caused by heavy strings and Martin’s lifetime warranty policy was bad for business. Heavier braces and a shorter scale length took some of the pressure off the bridge and cut down on warranty work. Unfortunately, it also took away some of the brash, sparkly character of the OM. And as the rest of the Martin line was gradually changed over to the popular 14-fret design, the OM designation was redundant and disappeared.

In the 1970s a fellow named Eric Schoenberg rediscovered the OM size and convinced Martin to make a batch of them for his store. They caught on among a guitar-playing public that had very few choices beyond the bass-heavy dreadnaught. Particularly with finger-style players, who played without a pick and appreciated the sparkly trebles and the even tone across all six strings inherent to the lighter, thinner design. As of 2012, the OM is as much the standard for acoustic finger-picking as anything else. Most guitar makers offer a guitar with similar specs, and (this is important), it’s fairly easy to find a case for this size guitar.

Very interesting, Kevin! The OM actually looks nice, too – I thought it would look like the weird old-cowboy guitars. Now I gotta hear one!

Come by the house soon and you can play one. If you have any weird old cowboy guitars, I’ll take them off your hands.