The sides come from your luthier supply house in the form of two slats, about 5 inches wide by 32 inches long and around 1/8 inch thick. I sand these down to about 0.085 inches with my drum sander before bending. Before I got that marvelous thing I had to reduce every board to useable thickness with a hand plane. Hand planes are great tools in the hands of great craftsmen. In my experience it’s a little different; they do the job fine, right up to the point that I think I’m almost done, and then, yep, the blade slips a half-hair and digs into the board and ruins it. One day I thought, “Life’s too short for this,” and ordered the sander. Bliss in all my days since.

So after sanding (in this case to 0.082 inches thick, as shown in the header photo), I use the block plane and a shooting board to true up the long edges so that they are flush with each other.

Then the critical decisions are made regarding which part goes where. The sides are bookmatched like the back. The long sides are mirror images, so that when glued together at the neck and tail, they have symmetric grain patterns. The tail ends are marked and the decision is made as to which edge meets the top and which side is the outside face.

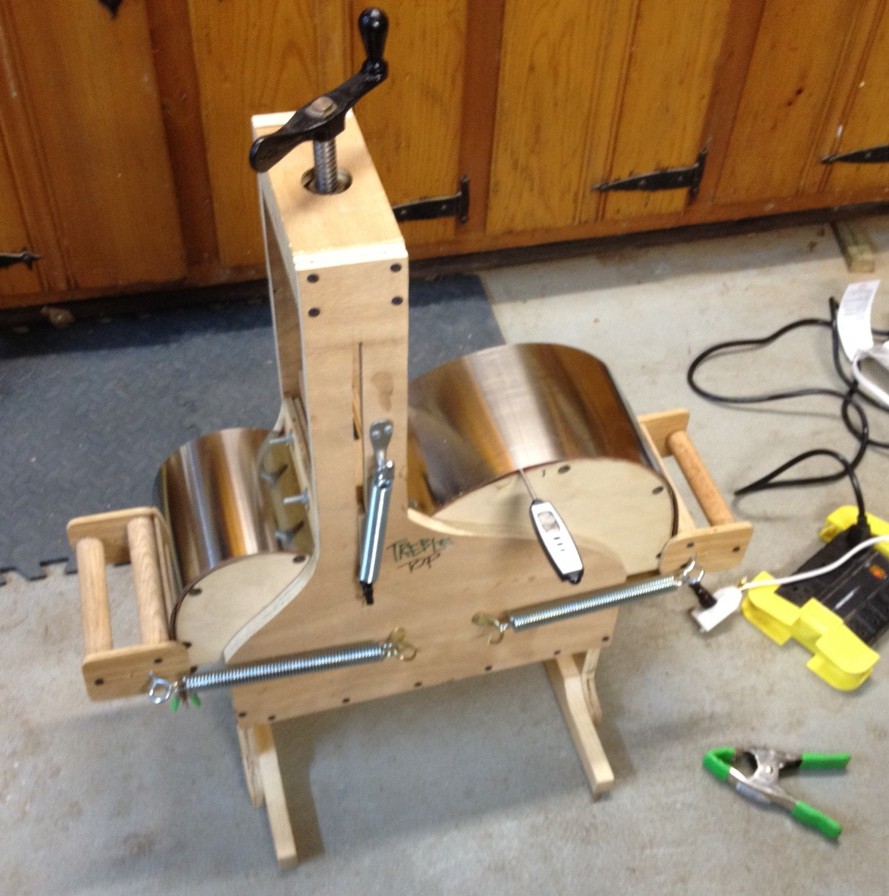

The sides are spritzed with water, or in this case, Super Soft II, a watery chemical (glycerine and water?) for softening wood veneers. Then prepared for the bender. The side bender is a plywood jig with clamps and a wine press screw. A mold in the shape of the side is inserted into the bender. Back to the side prep, the wet wood is covered by kraft paper, to keep the moisture and resins in, and then slipped between two spring-steel slats, 6 inches wide and 32 inches long. then a heating blanket of the same size is layed on this sandwich, and this is finally covered with another steel slat. This sandwich goes into the bender. The heating blanket, made of metal heating elements in a soft silicone cover, is then plugged in and turned on. As the heat passes 240 degrees, the water on the wood is turning to steam and causing the wood to turn rubbery enough to be bent into the shape we love so much.

As the wood begins to steam, the elasticity is such that we can start turning the crank slowly to bend the waist. After the waist is cinched, the lower bout and then the upper bout are bent down to the form. I leave a little space at the waist and fully tighten it only after the upper and lower bouts are bent. I have small handles attached to springs to hold the side sandwich to the mold’s shape. Keeping an eye on the thermometer, the sides cook at a temperature of no more than 300 degrees for the next ten minutes. This is the exact time that any distraction can result in fire. Too many guitar makers have stepped away to answer a phone or knock at the door and left the bender cooking and getting hotter and hotter. The blanket gets hot enough to ignite wood, and frequently does. After the cooking period, the side is allowed to cool and set in the bender over night.

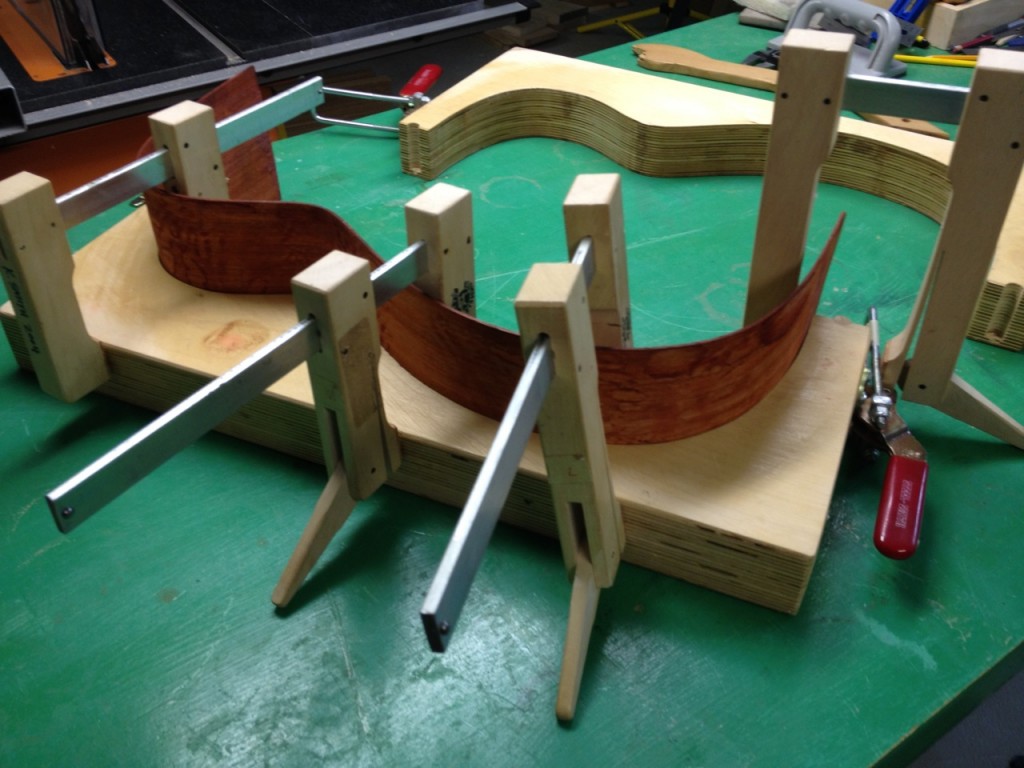

The next day, the sandwich is gently removed from the bender and the side is clamped into the guitar-building mold to keep it’s shape while the next side is bent. Note the amount of stain that was absorbed by the kraft paper. These padauk boards really bleed a lot. Maple purfling beware.

The next day, the sandwich is gently removed from the bender and the side is clamped into the guitar-building mold to keep it’s shape while the next side is bent. Note the amount of stain that was absorbed by the kraft paper. These padauk boards really bleed a lot. Maple purfling beware.